Steeplechase and hunt racing have long annals in the Empire State, and with more interest recently in turf racing, some long forgotten aspects of this history in New York are interesting to explore. Belmont Park staged extensive turf racing from the track’s opening until the late 1920’s, which played a critical role in getting New Yorkers through the political dearth of racing in the early twentieth century. The Daily Racing Form on April 5, 1926 stated:

“In thus preserving the sport in the face of the most adverse circumstances, the United Hunts won the praise of the greatest turf figures of America. The late Major August Belmont paid the association unstinted praise for the manner in which it had helped save the sport from eclipse in this country. . .”

New York State, due to its extensive canal network, vast agricultural lands, timber stands, and large urban population centers, has long been the location of equine breeding establishments. It is widely accepted that horse racing contests began on Long Island’s Salisbury Plain in 1665, only one year after British forces replaced Dutch colonial rule in New Netherland. The successful inception of thoroughbred racing at Saratoga Springs, before the Civil War had ended, led to the construction of numerous other race tracks, mostly in the metropolitan New York area and overseen by the Jockey Club, operating in the late nineteenth and into the early twentieth century.

The Empire State, the epicenter of racing in America, has also always been a hotbed for fervent politics, and individuals with lofty political ambitions and ideals. The election of Charles Evans Hughes as governor in 1906, over newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, ushered in an era of government-decreed morality. For a period of two years (1911-1912) racing did not occur, due to a ban on wagering, and those with equine interests were driven from the state until what had become a complicated legal issue could be settled. The newly imposed decency laws impugned the track directors, and made them responsible and punishable when wagering occurred.

The senior August Belmont emigrated from Germany in 1837 as the American representative of the House of Rothschild, married Carolyn Slidwell Perry in 1849, who was the daughter of Commodore Matthew Perry (not the Commodore Perry you were thinking of), and the niece of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry (the Commodore Perry you were thinking of), who routed British forces on Lake Erie during the War of 1812. Perry Belmont was the oldest of the three Belmont sons, his name a salute to his maternal heritage. The Belmont family included a daughter, Frederica, who was affectionately known as Betsy. She married Samuel S. Howland, who was manager of the Washington Jockey Club, founding member of the National Steeplechase and Hunt Association, and along with his brothers-in-law, was a principal in the construction of Belmont Park, and served as the managing director of the Westchester Racing Association when the facility opened and through its formative years. The United Hunts Racing Association from its inception used the mantra; “for sport’s sake and better sport.”

The Belmont Park Terminal Course staged numerous open and hunter steeplechases over the one-and-one-half-mile circuit, mostly competed by amateurs and sometimes in conjunction with the National Horse Show, in the years prior to the racing ban. The unique mile and a quarter flat turf course was popular with the Long Island hunt and polo set, and allowed polo ponies a chance to compete directly in speed trials known as ‘scrambles.’ The jump course had a reputation for being one of the stiffest in the country with the brush fences being a real challenge; the timber course for hunters had the same difficult reputation.

The throng was usually large and enthusiastic, and box parties abounded through the Belmont Park Terminal Course grandstand, which shared the same green and white color scheme as the main track. Also shared was the former Manice Mansion, a Tudor-Gothic edifice with castellated turrets, which faced Hempstead Turnpike and was the home of the Turf & Field Club, where legendary luncheons were served. The May 31, 1908 issue of the New York Times stated:

“Not only is Long Island the centre of racing ‘on the flat,’ but it has become the home of steeplechasing in this country.” The Times continued, “This field is regarded as being a natural steeplechase course, with its rough levels, fences, water jumps, and other varieties of going. It is considered by many to be, on a reduced scale, as fine a course as the famous Grand National near Liverpool, England.”

The patrons were treated to what might have been a horse racing first with what the New York Times of October 29, 1911 described thus: “Belmont Park Terminal yesterday was the scene of the most up-to-date method of ‘going to the races’ when a descent was made upon the racetrack inclosure by means of airships, marking a new epoch in the history of the ‘sport of kings.’ With the dropping of the two biplanes, each of which contained a woman passenger, society for a moment lost all interest in the thoroughbreds and bubbled over with interest concerning the novel method of invasion.” Another pioneering feature, and perhaps the birth of simulcasting, albeit without video, was tried out when a special telegraph line was run from Churchill Downs. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle of May 11, 1916 reported:

“The running of this race will be described by megaphone for the special benefit of those who have horses running in the Kentucky Derby as well as at Belmont Park Terminal.”

These revised legal developments, however, signaled to some, such as Willis Sharpe Kilmer of Binghamton, that the time was right to begin a breeding operation in upstate New York, as the sport rebounded from ill-conceived governmental interference. Certainly Mr. Kilmer was not the only one holding this view, as John Sanford and his family had continued success with their breeding operation high above the Mohawk River at Hurricana Stud near Amsterdam. Other successful operations were Gifford Cochran’s Runnymeade Stable at Mt. Kisco, James Butler’s Eastview Stud near Tarrytown and Robert L. Gerry’s Aknusti Farm near Delhi. Mr. Gerry’s sense of humor shows through with his choice of the name Aknusti, which is the Iroquois word for ‘expense,’ bringing to mind the old adage: “how do you make a million dollars in horse racing? Invest ten million.”

The United Hunts Racing Association held a meet in the spring months and an autumn meet, which often was scheduled to occur between the end of the Saratoga season and the opening of the Belmont Park season. The Belmont Park Terminal Course often staged army or military races, with varying conditions limited to active duty troops, and regularly contested by uniformed officers of various nations. Lieutenant George S. Patton competed in several military events staged at Belmont Park Terminal during the autumn of 1912. The future general, who later earned the sobriquet ‘Old Blood & Guts,’ was competing in equestrian events then, having just returned from the Stockholm Olympic Games representing the United States, where he finished fifth in the Modern Pentathlon (swimming, shooting, fencing, equestrian and athletics).

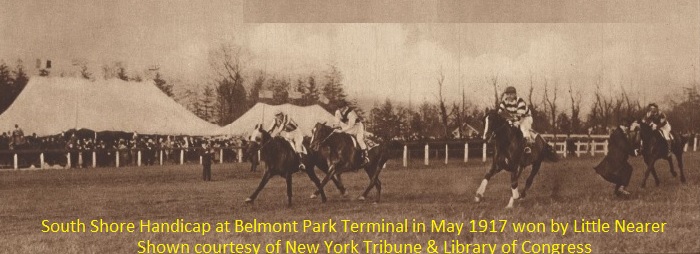

During the first week of April 1917, as the United States Congress was preparing a Declaration of War on Germany, a tremendous conflagration occurred at Belmont Park and damaged the three-storied, balconied clubhouse and destroyed the grandstand and many other buildings, including the Belmont Park Terminal Course grandstand, jockey quarters and train terminal. The fire was a deliberate act, simultaneously originating in six separate locations during the early hours of the morning, with kerosene soaked cotton wadding used as an ignition source, and beer bottles filled with acid placed to injure and deter responding fire fighters. During the War, several acts of sabotage occurred on American soil, including a large explosion of munitions barges in New York harbor that caused the original structural damage to the arm and torch of the Statue of Liberty. A second deliberate fire erupted at Belmont Park just a few weeks later, destroying many of the barns. Unfortunately 26 race horses and two ponies, mostly untested 2 year olds, were lost in this blaze. Several acts of terrorism had occurred in the United States prior to America’s entry as an Allied combatant against the Central Powers, and many considered this deliberate torching another such episode. With many of the functions of the track curtailed by the ruined buildings, it was decided to operate as originally planned and amazingly racing resumed with the use of circus tents, carpeted with heavy cocoa matting, for the comfort of the patrons of the turf. The Daily Racing Form reported on May 11, 1917:

“The recent work of the incendiaries, which destroyed the new grandstand, will not affect the viewpoint of the spectators to any great degree at the Belmont Park Terminal Course. Arrangements have been made whereby the midfield will be thrown open at the end.”

Some of thoroughbred racing’s biggest stars of that era gave the Terminal flat turf course a whirl, including Papp, Cudgel and Kentucky Derby winner Exterminator. The Daily Racing Form of May 29, 1918 in reporting the Turf and Field Highweight Handicap, the next start for ‘Old Bones’ after shedding the garland of roses:

“Exterminator plainly showed that he did not like the turf course and failed to respond when called on in stretch, finishing a length behind the winner.”

Detailing the Turf and Field Handicap results in the New York Herald from May 26, 1918, during a time our nation was involved in a war in Europe and experiencing the awful effects of a global pandemic is the following article. The headline is exciting: “Society enjoys horsemanship at the United Hunts Meet At Belmont Park Terminal; Army Officers Display Skill In Saddle In International Military Race – Exterminator Runs Second.” The article really draws in a race fan, of any era, with the description of that day,

“Coincident with the spring meeting the Turf and Field Club reopened its hospitable doors, and the memory goes back in vain over many years of experience in the social side of race days to recall a similar incident of greater animation or more varied interest. It was decidedly a military scene, which Lander's Band accentuated with its opening march, played under the tall trees of the lawn. It was called "For the Freedom of the World." Of course “The Star Spangled Banner" started the programme and it was in keeping with the spirit of the occasion that "God Save the King"' and the "Marseillaise" followed. "Smiling Sammy," a fox trot, "Don't Try to Steal the Sweetheart of a Soldier," another march, and "Hello, Central! Give Me No Man's Land," one of Al Jolson's songs, were in keeping with the lighter side of this notable spring race meeting. Accustomed colors in civilian attire were lost in the dominant shades of olive drab of American uniforms, the multiple colors of the British and the horizon blue of the Italian uniforms. More than fifty officers in various branches of the allied service were among the guests at the club luncheon which prefaced the first race. . .”

It seems incredible that the Kentucky Derby winner was entered in an event offering a $700 purse to be run on grass, and indeed the New York Times report of the race stated, “The presence of the Derby winner overawed many of the owners.” It must be assumed that Exterminator’s owner, Willis Sharpe Kilmer, was committed to making the hunt meeting a success for the sponsoring association. The same New York Times article continues,

“The United Hunts, which determined to keep up amateur racing by running its meeting, while the other associations waited for less troublesome times, had every reason to be pleased with the stand taken. There never was a more successful meeting held by amateurs and one that brought out more high class horses, both on the flat and over the obstacles. The Long Islanders turned out in force to give countenance to the continuance of the sport, and the special trains from New York were well filled by racing enthusiasts attracted by the races, which fulfilled all the promise of excitement given by the entries.”

“A fleet of Fifth Avenue [double-deck] buses will handle the overflow crowd of the box-seat applicants for the United Hunts Racing Association Spring meeting at Belmont Park Terminal on Thursday and Saturday.

Another benefit of the Terminal Course was its function as a schooling ground for jumpers, while sharing stabling facilities and other equine services with the main track. The immeasurable economy of scale provided by keeping jumping stock with other racers cannot be understated. Certainly farrier services, feed delivery, veterinary visits and manure removal were all simplified by this incorporation. The April 26, 1923 Morning Telegraph reported,

“That the sport of steeplechasing in this country is in for an expansion that will place it where it rightfully belongs as a racing test is evident from recent happenings, the latest and most important being the establishment at Belmont Park Terminal of a permanent development ground for chasers by the Westchester Racing Association. President Joseph E. Davis of the National Steeplechase and Hunt Association has been largely instrumental in the importation of desirable jumping material this Spring. Some of the horses have been already contracted for by enthusiasts who needed little encouragement to become active participants, instead of onlookers, in a branch of sport which numbers its devotees by the hundreds of thousands all over the world. Mr. Davis found a powerful ally in the person of President August Belmont of the Westchester Racing Association, and between them cross-country conditions may be expected to show improvement. The Westchester management has always shown its willingness to promote the highest type of cross-country racing.”

The magnificent silver trophy shown above was awarded in May 1921 to the owner of Roudy, ridden by W Lyon, for victory in a Belmont Park Terminal race on 21st May 1921. If anyone has any further details about the race then contact Michelle McPeek mmcpeek77@gmail.com

The Belmont Park Terminal Course continued to operate in the 1920’s, with the plant maintained in the best regard. The Daily Racing Form of April 19, 1926 mentioned:

“The various courses at the Terminal are in superb condition for the meeting. Horsemen who have been schooling their jumpers over the steeplechase ground are pleased with the going and the placing of the obstacles. The turf on the flat course has been rolled persistently and it compares favorably with that in England.”

In the years following the death of August Belmont II in 1924, and his brother-in-law Sam Howland in 1925, the Westchester Racing Association, which had always operated the Terminal Course in parallel with all other racing functions, began to weigh options. The management decided to develop the portion of the property south of the Hempstead Turnpike, which contained the Terminal Course, into a residential community. The New York Post of May 18, 1927 reported,

“Joseph E. Widener is proud of Belmont Park. And the president of the Westchester Racing Association, who was host at a luncheon to turf writers yesterday, has full reason to be. . . Mr. Widener let it be known that in due time he intended disposing of certain property known as Belmont Park Terminal and using the proceeds of the sale, probably not less than $2,500,000, as a fund for the endowment of the more important stakes of the spring and fall meetings. This, he feels, would perpetuate racing for all time, no matter what happens.”

The mitigating factor in this decision was unsurprisingly, money. By the late 1920’s the Westchester Racing Association’s Belmont Park was being bested by purses offered at the Maryland and Kentucky tracks, which derived great profits from their pari-mutuel machines. New York State would not adopt pari-mutuel wagering until 1940, after many years of painful wrangling in Albany. In order to attract the best competitors back to Belmont Park, the Terminal Track would be sacrificed.

“Belmont Park Terminal, the home of the United Hunts Racing Association, is doomed. . . When Major Belmont was president of the Westchester Association he permitted the amateurs to hold sway at Belmont. . . Under the leadership of John McEntee Bowman, president of the association, the amateurs held meetings that were in every way as good and successful as the professional meetings.”